When Your Childhood Safe Space Has Become a Place to Take Advantage of Them

Video games helped me navigate a relationship with neurodivergence. My neurodivergent children also love video games...but I worry about them.

I wouldn’t be diagnosed as autistic until well into my 20s, but video games provided a realm to grapple with a world that always seemed askew to my logic.

Because my brother was seven years older than me, I had an NES controller in my hands before I could walk. Like life, NES games were hard to grasp. Rules and expectations seemed to exist without logic or explanation. But in games, I could fail over and over without letting anyone besides myself down. It taught me to persevere, that I could overcome hardships if I came at them with a certain mindset to “figure them out.”

It was a gift I’d hoped to share with my kids someday.

Two years ago, I was childless. Today, I help raise three kids, ranging from ages nine to 17, in a communal home of seven. All three are neurodivergent in their own unique ways, and my obsession with video games has seeped into them.

But the gaming landscape they're exploring is much different than what I had, and I've learned from painful, personal experiences that what exists today hopes to take advantage of people like us. People who "love too much,” too openly. People who grapple with hyperfixations and put everything into a new thing they love. People who treasure experience more than money.

Utilizing social cues and fine-tuned body coordination are two of the most common hurdles for neurodivergent groups in average society. Luckily, my journey to become a storyteller/writer sent me on my lifelong, cross-country journey to understand people, and many cues came with that. But for my hands' dexterity? To cope with the daily strain of a world built to overwhelm? To just survive with some happiness in my heart? The only answer was video games.

But it wasn’t just game difficulty that held back my passion. The simple act of controlling onscreen characters bordered on physically painful. I struggled with pencils and shoelaces long after my peers. Dropping things was just a common expectation from me. I'm grateful that my family was largely graceful about that.

The toughest aspect of my parenting position has come from a lack of context for their gaming upbringing. Remember, these kids are older. They’re already well on their way of forming the people they’ll become, so I can’t start at square one. But it’s clear that those experiences leave a gap in context for the worth of playing older, more precisely demanding games.

I’m left to effectively throw out everything I’ve learned to help them.

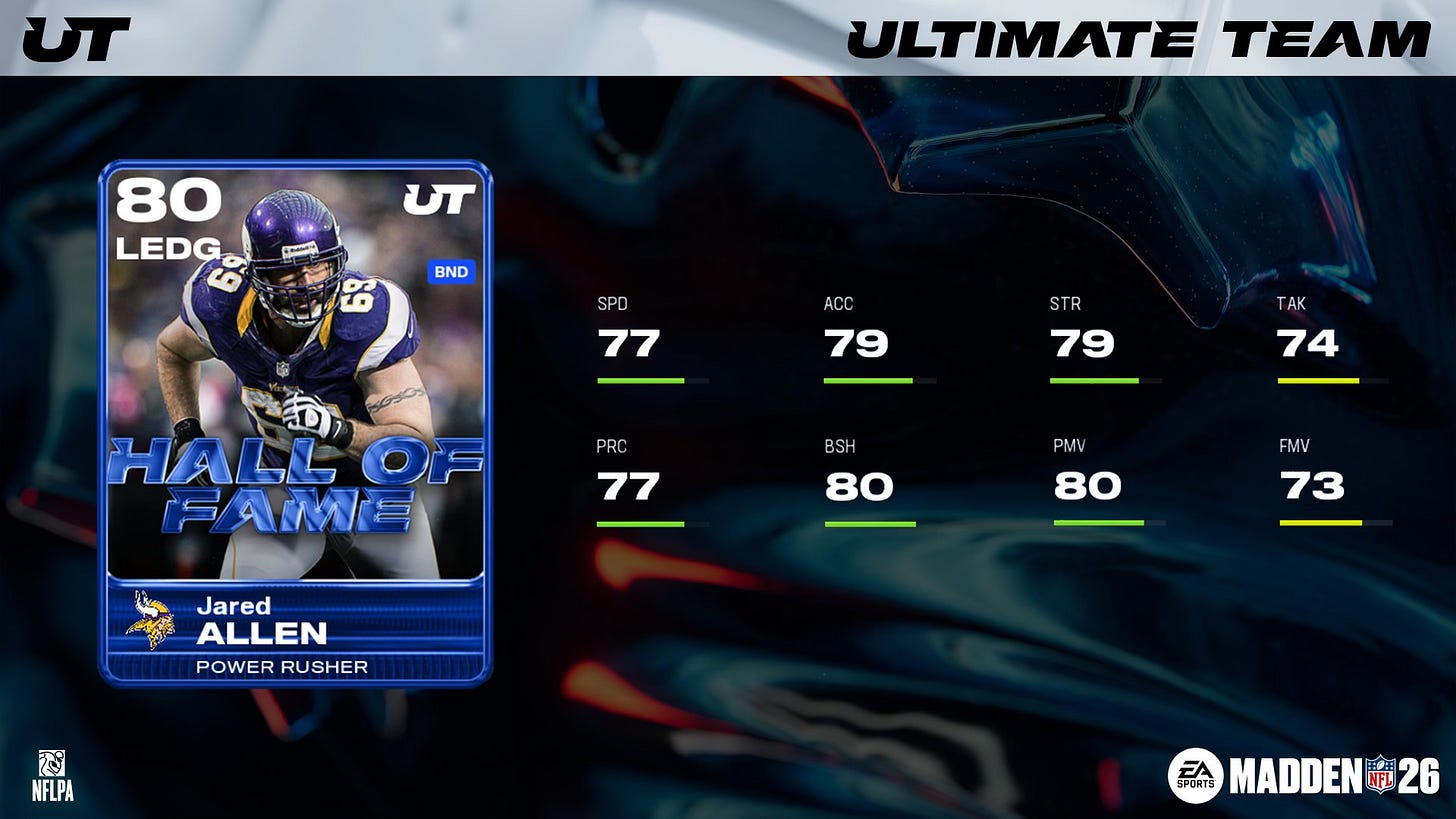

The methods of pushing aggressive monetizations to my kids wriggles deeper into their daily lives. I’ve winced as our youngest has fallen in love with FIFA and NFL. He hasn’t shown an interest in Madden, yet. And luckily he’s enjoying a FIFA game from last decade, where the Ultimate Team hooks are long dead. But every day feels like a step closer to a diverging point where his desires will become wrapped in these spaces where I can no longer protect him. I dread that day.

I always had to hit both flippers when playing pinball. Hadoukens were a continuing challenge for my hands, nearly a decade after learning the combination. And once the Nintendo 64 controller came around, I could only use it with my hands clutching the ends while my 11-year-old thumb reached all the way to the center for the analog stick. To this day, it's still the only way I can play one of my favorite consoles.

With the PlayStation 2 generation came manipulating both joysticks independently, my next painful learning experience. At least with this one, I watched plenty of others struggle just as much. But even still, video games gave me a place to try and fail. It gave me a place to curse myself and my perceived shortcomings, recompose and do it again. And again.

I’m proud of how my efforts paid off. Now, I'm that guy who can run up the Super Mario Bros. stairs and launch for the flagpole without slowing. Beating Contra: Shattered Soldier on PlayStation 2 without me or my friend losing a single life was my "crowning glory." I can do coin tricks across my knuckles. I learned to drum.

The lessons of my youth, though, are not the lessons for my own kids.

“The methods of pushing aggressive monetizations to my kids wriggles deeper into their daily lives. I’ve winced as our youngest has fallen in love with FIFA and NFL. He hasn’t shown an interest in Madden, yet. And luckily he’s enjoying a FIFA game from last decade, where the Ultimate Team hooks are long dead. But every day feels like a step closer to a diverging point where his desires will become wrapped in these spaces where I can no longer protect him.”

My upbringing was defined by video games being a safe space for me to improve, explore and discover myself. I wish that love for a bygone era wasn’t leading my kids directly into a space of manipulation and predation, a reality I learned the hard way.

Overwatch wasn’t my first experience feeling taken advantage by a game, but it was the one that changed my life. Autism brings with it an innate desire to recognize and do what is expected of you. Maybe it’s because we notice how easy that is for most others—and overcompensate. But the more you love what’s doing the asking, the more it matters to you.

So when you spend many hundreds of hours playing a game you adore, and it clearly wants you to buy their loot boxes… Perspective can be lost. When I got mine back, all I could see was the time evaporated and the thousands of dollars burned.

One rule in our house: with new games, we must wait a handful of months after their release, in case they add microtransactions. I’ve watched them become more patient. I mock games that haphazardly add new internal stores. Making them laugh at these things has managed to flip the experience from disappointment over missing out, to laughing at companies’ ill-considered money grabs.

For all the ways I’ve been unable to provide a smooth and safe path to enjoy new games, I’ve been grateful to at least see them recognize it as a failure of the studios forcing these decisions, rather than any shortcomings in themselves.

Really appreciate this relatively unique perspective you shared, Matt. It not only adds a layer to the usual "videogaming when a kid" tales, but a different view on how things such as loot boxes, and the nearly-always-connected games of today can be so different than the nearly-always-off games of yesteryear. Thank you for sharing and good luck to you and your house of bustling joy!

This is incredibly relatable, especially as a coach/mentor to middle and high school students with brain chemistries all over the map and adoptive parent to an ND kiddo.

He's still at an age where we have a lot more control over the games he's playing than we will when he's older, but trying to find ones that will be challenging in ways that teach can be so difficult. And guiding him toward those rather than the mind-numbing dopamine-machine games is another challenge on top of it.

It's good work you're doing, though, and worth the effort, even (especially) on the hard days!